Designing a course from scratch is no easy task. And when the subject matter is changing constantly, you have a real challenge on your hands.

But that’s what two assistant professors at the School of Nursing and Health Studies, Joseph Lightner and Sharon White-Lewis, did for the fall 2020 semester.

“When we realized this was a pandemic and something the world knew little about, those of us in public health said, ‘Someone should teach a course about this.’ And then we realized ‘someone’ was us,” said Lightner, who holds a master’s in public health and a doctorate in kinesiology and leads the nursing school’s bachelor of public health degree program.

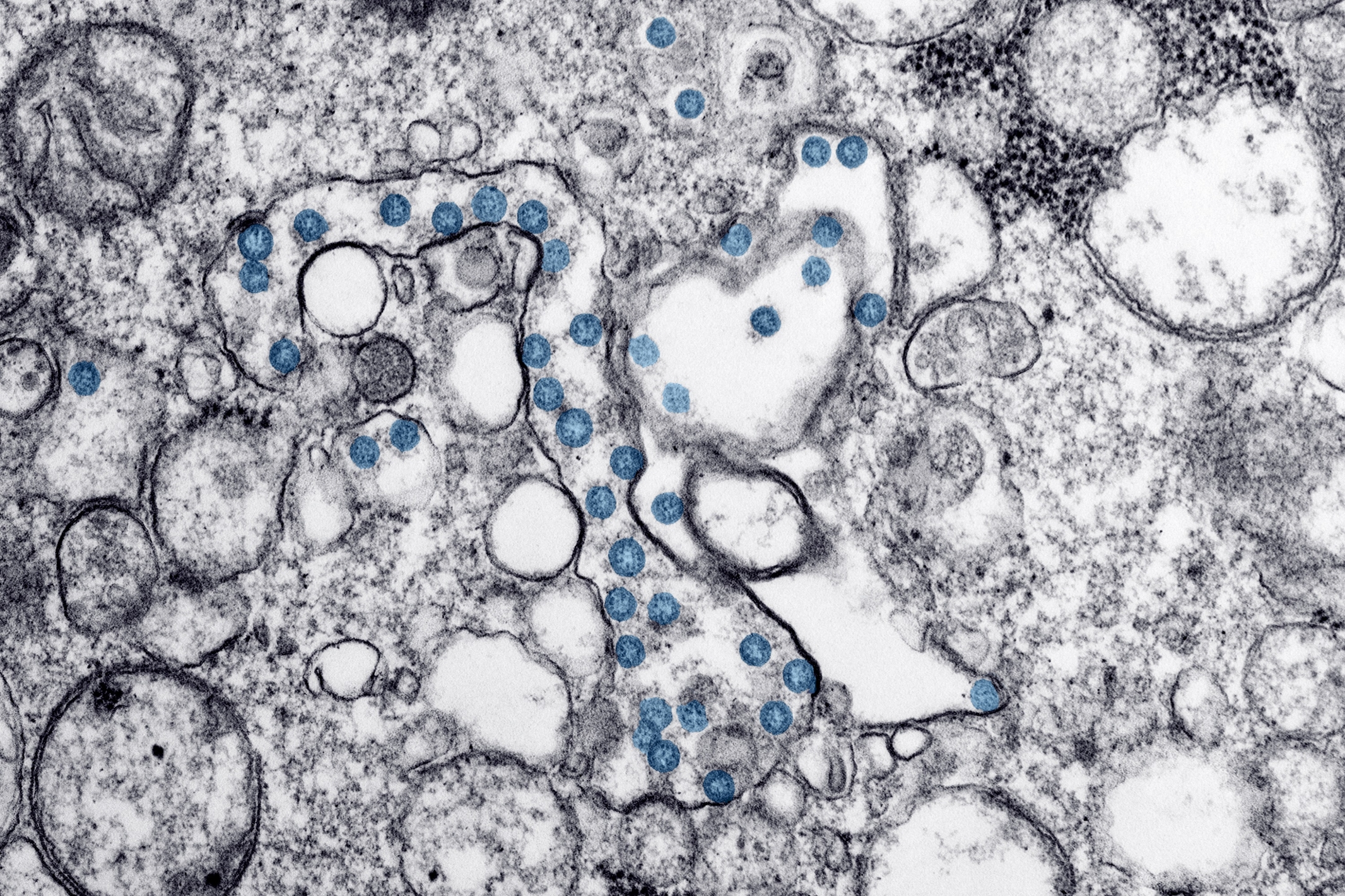

So he and White-Lewis, whose expertise includes disaster preparedness and response, designed a comprehensive course on the COVID-19 pandemic. It covered a lot of ground, from the history of the 1918 flu pandemic to what the coronavirus is, how it spreads and how it acts in a body, to COVID-19 treatments and vaccines, contact tracing and the country’s emergency preparedness and response in the first nine months of the pandemic.

Teaching about an unfolding pandemic also was a new challenge. White-Lewis said they frequently reacted to developments, quickly gathering reliable information and incorporating it into lectures and exercises.

From left, Assistant Professors Joseph Lightner and Sharon White-Lewis taught the course to 37 students including Lejla Skender and Denise Dean.

Everyone in the class took an online Johns Hopkins University course to become certified contract tracers. They also worked in teams to try to determine who brought COVID to the White House reception for Supreme Court nominee Amy Barrett Cohen.

“That was a fascinating exercise,” said Denise Dean, a senior working on a health sciences degree with a concentration in public health. “We worked in teams with data on everyone in attendance: when they showed symptoms, when they tested positive and had tested negative, and other activities they had engaged in. We had numbered photos, too, to show which people were close to each other.”

Dean, who has done research projects of her own and is an undergraduate research assistant, added, “We had learned in lectures when people are most contagious in relation to when they show symptoms, which helped us narrow the possible carriers.”

Lightner said the teams were able to determine three people in attendance who were the most likely to have brought the virus to that group of key government officials, though with this virus it could have been someone else who showed no symptoms. “That’s another thing the students learned: Public health can be messy and complicated,” Lightner said.

Your final: What do you do when a pandemic strikes?

The final exam was a drill on responding to a pandemic, said White-Lewis, who advised those who drew up the Kansas City area’s vaccine distribution plan and leads the area’s nine-county Medical Reserve Corps, a network of medical and public health volunteers.

Lejle Skender, a senior biology major considering medical school, said, “It was great to learn how all the parts of the medical system need to work together — who’s doing what behind the scenes to make sure people and materials are available in the right places.”

Dean added: “And we learned what happens when there’s an emergency and a good plan isn’t in place.”

The course had wide appeal, drawing 37 students, including nursing graduate students and undergraduates from majors including nursing, pre-pharmacy, public health, health sciences and biology. That student mix provided some challenges, Lightener said, “because we had to make sure the undergrads had enough of the basic sciences to understand when we got into the etiology, epidemiology and pathology of the virus and the disease.”

It also gave students access to dozens of other perspectives, especially on discussion boards that White-Lewis posted.

“The class was a big jumble of backgrounds and majors, but we all had the goal of learning about this virus and how that knowledge could benefit us in our careers,” Skender said. “We all learned from each other because, for example, some of us started with more science knowledge to share, and the graduate student nurses gave us a lot of information from their perspective as nurses.”

She added, “If the course is taught again, I would recommend it to anyone interested in a health care career.”

“That’s another thing the students learned: Public health can be messy and complicated.”

White-Lewis, who earned her doctorate in nursing from UMKC in 2018, said the student discussions were valuable and enriching but often difficult.

“In the module on vaccines we did a discussion where they had to take 10 of their family and friends and decide who gets the five vaccine doses available and who could die,” White-Lewis said. “For me, it was really hard hearing from students who had family members who have died of COVID, and how they wished that everyone would take the virus much more seriously.”

Lightner said that it would be great to offer the course again, but that that did not seem possible without more resources dedicated to it. “It was great to develop the course and fit it in somehow last fall,” he said. “But Dr. White-Lewis and I both are research faculty who have to do our own research. I’m director of our public health degree program, and she teaches graduate research and has her emergency response and other duties.”

Whether the course can be taught again, Lightner said, “I think it’s clear this information is vital. However well the vaccines do, the evidence is mounting that practitioners are going to be dealing with COVID and its long-term effects for years to come.”